Investment in infrastructure to cater for some 19 million visitors per year is top priority. At the same time authorities aim to leverage “unique and diverse heritage of natural and archaeological sites” to attract discerning global travellers in search of something out of the ordinary

Some day there will be nothing odd about hearing Saudi Arabia talked about as a tourist destination. The transformation, when it comes, need not be a lengthy one.

After all, agrarian Spain required less than a decade to reconfigure itself as the world’s third-ranked destination for foreign visitors.

But it did so by attracting the sun, sand and sangria crowd, a path you can be sure the Saudi authorities are not interested in exploring.

“Endowed with a unique and diverse heritage of natural and archaeological sites, Saudi Arabia could potentially attract the most sophisticated global travellers,” says Dr Costas Verginis, Senior Director of Development for the Marriott hospitality chain.

“Not mass numbers, but a few hundred thousand of discerning travellers from across the world for whom travel is closer to a scientific and academic endeavour than a leisurely tour. Saudi Arabia is in the best position to redefine tourism.”

Virgin beaches along the rim of the Red Sea are a natural draw for divers and surfers, while exclusive resort facilities could be developed at Dammam, on the opposite side of the peninsula.

Not to be missed by even the most casual visitor are the spectacular ruins at Mada’in Saleh, most of which were left there by the Nabaeteans, the ancient people responsible for the breathtaking “rose red” city at Petra in Jordan.

The Arabian peninsula was culturally shaped and enriched by the caravans linking the Mediterranean world and the Far East, passing through trade hubs such as Najran, near the Yemeni border, famous to this day for its traditional souk (market) as well as its architecture incorporating details from merchants’ places of origin.

Nearly 3,000 archaeological sites from different civilisations and eras, including a surprisingly active prehistoric period, are being examined, catalogued and placed under government protection, with stone tools from the Shuwayhitiya site dated at over a million years old.

But why single out for priority development a sector that at present represents just a 4.3 per cent total (1.6 per cent direct) contribution to GDP? Because it can best be addressed in conjunction with two closely related problems appearing high up on the nation’s to-do list.

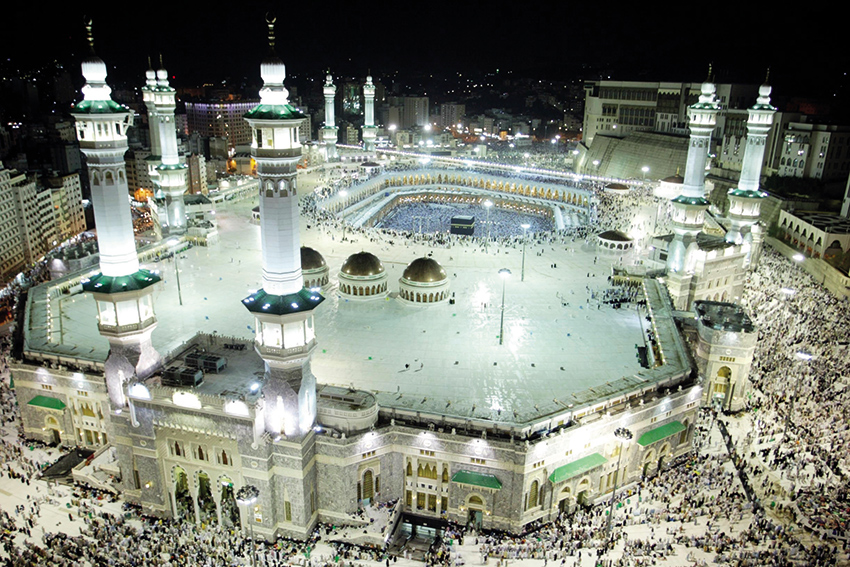

In recent years, what used to be a relatively manageable influx of religious pilgrims has become a gushing torrent the Saudi authorities admit they were not prepared for.

Now the country is hosting some 19 million visitors per year, including pilgrims, business travellers and family members of foreigners working in the kingdom under contract, etc.

They are not quite tourists, properly speaking, but in many respects their needs are similar.

It has come to the point where only passengers with confirmed bookings are allowed in the terminal at King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah, the point of entry closest to Mecca and Medina that handles 6 million passengers per year.

A Spanish consortium is reportedly having trouble finishing the $30 billion rail link between the three cities. New metro lines and premium hotels are under construction in Riyadh and Jeddah, but a plan to issue tourist visas was scrapped a few months after it was introduced last year.

“Given the constraints of existing infrastructure, the government has had to limit the allocation of visas for pilgrims. I think the aim is to issue 20 million visas by 2020,” says Abdullah bin Nasser Al Dawood, CEO of the Al Tayyar Travel Group, which specialises in religious travel.

“That is almost five times as many visas granted now to Muslims worldwide, excluding domestic pilgrims and citizens of Gulf Cooperation Council countries who are not required to have them.

So the government is spending hundreds of billions of dollars on infrastructure,” adds Mr Al Dawood, whose firm just acquired its first British travel agency.

The other determining factors are tourism’s impact on economic diversification and the employment it creates for the coming generation of Saudi citizens who are arriving now in numbers far greater than the job opportunities that may be available to them when they finish their studies.

So tourism in Saudi Arabia is a long-term proposition, but the groundwork that will someday sustain it is being laid right now by the Supreme Commission for Tourism and antiquities, whose chairman, Prince Sultan Bin Salman Bin Abdulaziz, has committed to creating an “environment for investment” through drafting a regulatory framework, offering incentives for general and targeted investment, and devising long-term strategies for recruiting and training personnel in the hotel and hospitality sector.

0 COMMENTS